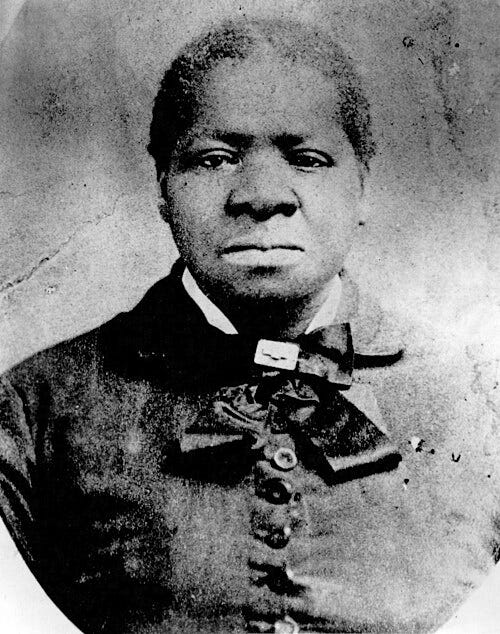

Biddy Mason: From 1,700-Mile Trek in Chains to California's First Black Female Real Estate Magnate

Walking to Freedom: How an Enslaved Midwife Became Los Angeles' Wealthiest Black Woman and Built the City's First Black Church

Bridget “Biddy” Mason stands as one of the most extraordinary figures in American business history—a woman who walked 1,700 miles behind a wagon train while enslaved, sued for her freedom in a landmark California court case, and transformed herself into Los Angeles’ wealthiest Black woman and one of the city’s most beloved philanthropists.

In 1848, at age 30, Mason walked nearly the entire 1,700-mile journey from Mississippi to the Salt Lake Valley, traveling behind a 300-wagon caravan.

Born into slavery on August 15, 1818, in Hancock County, Georgia (though her exact birthplace and birthdate remain uncertain), Mason learned the skills of herbal medicine, midwifery, childcare, and livestock management from other enslaved women—knowledge that would prove invaluable throughout her life.

Mason’s enslaved life took her from Georgia to Mississippi, where she became the property of Robert Marion Smith and Rebecca Dorn Smith.

In December 1855, fearing his “property” would be seized, Smith decided to move his enslaved people to Texas, where slavery remained legal. But Mason’s free Black friends intervened…

As a young woman, she gave birth to three daughters—Ellen (born around 1838), Ann (born around 1844), and Harriet (born around 1847)—whose fathers remain unknown, though some historians speculate Smith may have fathered at least one child. When Mormon missionaries converted the Smith family in 1847, the household joined the great Mormon migration westward, and Mason’s ordeal began.

In 1848, at age 30, Mason walked nearly the entire 1,700-mile journey from Mississippi to the Salt Lake Valley, traveling behind a 300-wagon caravan.

Along the route, she bore crushing responsibilities: setting up and breaking camp, cooking meals for the entire party, herding cattle, serving as midwife to women in the caravan, and caring for her three young daughters aged 10, 4, and a newborn—all while walking the dusty trail.

Despite being illiterate herself, Mason recognized education as crucial for Black advancement

Her midwifery skills were in constant demand, and she reportedly delivered dozens of babies during the arduous trek.

In 1851, Mormon leader Brigham Young established a new community in San Bernardino, California, and Smith relocated his household once again, ignoring both California’s 1850 constitutional prohibition of slavery and Young’s warnings about bringing enslaved people to a free state.

For five more years, Mason remained illegally enslaved in California, working Smith’s cattle ranch along the Santa Ana River.

During this time, she befriended free Black Californians Charles H. and Elizabeth Flake Rowan, and later Robert and Charles Owens (father and son), who informed her of California’s free-state status and urged her to contest her enslavement.

In December 1855, fearing his “property” would be seized, Smith decided to move his enslaved people to Texas, where slavery remained legal. But Mason’s free Black friends intervened, alerting Los Angeles County Sheriff Frank Dewitt to Smith’s plan.

The sheriff intercepted Smith’s wagon train carrying a writ of habeas corpus and placed Mason, her three daughters, her companion Hannah (also enslaved by Smith), and Hannah’s children—14 people total—into protective custody until their case could be heard.

On January 19, 1856, Mason’s freedom petition came before Los Angeles District Judge Benjamin Hayes in the landmark case Mason v. Smith.

Although California law prohibited Black people and Native Americans from testifying against white people in court, Judge Hayes allowed Mason to speak—an extraordinary departure from standard practice.

After three days of proceedings, on January 21, 1856, Judge Hayes ruled that Smith “intended to remove [Mason and the others for] his own use without the free will and consent of all or any of [them], whereby their liberty will be greatly jeopardized,” and declared all 14 petitioners free.

The ruling was the first of its kind in California and established crucial precedent for future freedom cases, coming a full year before the infamous Dred Scott v. Sandford decision that ruled enslaved people could never become citizens. At age 38, after spending nearly four decades in bondage, Biddy Mason was finally free.

Mason immediately moved her family to Los Angeles, a town of only about 1,600 people.

She found work as a nurse and midwife with Dr. John S. Griffin, a prominent local physician, earning $2.50 per day—exceptional wages for a woman, particularly a Black woman, in the 1850s. Mason spoke Spanish fluently, making her invaluable to Dr. Griffin in treating Los Angeles’ diverse population.

Her skills as a healer and midwife earned her widespread respect, and she became known for delivering hundreds of babies to mothers of all races and social classes throughout Los Angeles County.

For ten years, Mason carefully saved her earnings, living frugally while studying Los Angeles’ rapidly developing real estate market. In 1866, she made her first land purchase—paying $250 for nearly an acre of land on Spring Street between Third and Fourth Streets (in what is today downtown Los Angeles near Broadway).

At the time, this area was considered “out of town,” with a irrigation ditch running through the property and a willow fence encircling it. Her daughter Ellen recalled that Mason firmly told her family that “the first homestead must never be sold”—she wanted her family to always have a home they owned.

But this first purchase was only the beginning.

In 1868, Mason bought property on Olive Street. She continued acquiring parcels strategically as Los Angeles boomed, eventually owning properties on Spring Street, Broadway, Eighth and Hill Streets, and throughout both the east and west sides of Los Angeles.

As the pueblo exploded into a city, Mason’s formerly rural lots became prime downtown real estate. In 1884, she sold the north half of her original Spring Street property for $1,500—six times what she paid—and built a two-story brick commercial building on the remaining half, renting the first floor to businesses while living in an apartment on the second floor.

That same year, she sold her Olive Street lot for $2,800, more than seven times her original purchase price of $375. One plot she purchased for $250 eventually sold for $18,000. Mason never learned to read or write, signing all her deeds with a flourished “X,” yet she possessed an extraordinary ability to analyze property market trends and identify desirable locations for investment.

By the time of her death on January 15, 1891, at age 73, Mason had amassed a fortune estimated at nearly $300,000 (approximately $7-10 million in today’s dollars), making her the wealthiest Black woman west of the Mississippi River.

More remarkably, the land she owned in downtown Los Angeles is now worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

Yet Mason’s legacy extends far beyond her business acumen. Known as “the Grandmother of Los Angeles,” she was legendary for her generosity. Each morning, people in need lined up outside her Spring Street gate seeking food, shelter, medical care, or financial assistance—and Mason rarely turned anyone away.

During the devastating floods of the early 1880s, she gave an open order to a local grocery store authorizing them to supply all families made homeless by the flood with groceries, which she cheerfully paid for.

Mason donated to churches attended by both Black and white congregants, visited prison inmates with gifts and aid, founded a traveler’s aid center, and was instrumental in establishing an elementary school for Black children.

In 1872, she and her son-in-law Charles Owens (who had married her daughter Ellen) co-founded the First African Methodist Episcopal Church of Los Angeles (FAME)—the oldest Black church in Los Angeles and today a megachurch with over 19,000 members.

The organizing meetings were held in Mason’s Spring Street home, and she donated the land on which the first church building was constructed.

When Mason died, she was buried in an unmarked grave at Evergreen Cemetery, likely because of the intense family dispute that erupted over her substantial estate.

The “Mason Block” eventually passed to her grandson Robert Curry Owens, who became the wealthiest Black man in Los Angeles County and managed to keep the family’s cherished “first homestead” until the Great Depression.

Mason’s grave remained unmarked for 97 years until March 27, 1988, when the mayor of Los Angeles and members of FAME Church held a ceremony erecting a tombstone in her honor.

In 1989, a Biddy Mason Memorial Park opened at 333 South Spring Street featuring an 80-foot concrete wall timeline by artist Sheila Levrant de Bretteville chronicling Mason’s extraordinary life.

In 2013, her descendants established the Biddy Mason Charitable Foundation, which provides scholarships, housing, and support services to current and former foster youth in Los Angeles County—honoring Mason’s legacy of serving vulnerable populations.

Historical Significance to Black Business in America

Biddy Mason’s transformation from enslaved midwife to California’s first Black female real estate magnate represents a watershed moment in African American business history, demonstrating how formerly enslaved women leveraged specialized skills, strategic real estate investment, and community building to achieve unprecedented wealth and influence in the post-emancipation West.

Pioneer of Black Female Real Estate Entrepreneurship

Mason emerged as one of the earliest and most successful Black female real estate investors in American history during an era when multiple barriers prevented women—especially Black women—from property ownership.

Under the legal doctrine of coverture, married women could not purchase real estate, enter contracts, or control their own earnings. For Black women, additional layers of discrimination made property acquisition nearly impossible.

Yet Mason navigated these obstacles with extraordinary skill. Her real estate portfolio placed her among Los Angeles’ wealthiest residents regardless of race or gender.

By 1870, only three Black women in Los Angeles owned property, compared to eleven Black men—and Mason owned more property than nearly all of them. Her success occurred during a narrow window of opportunity: before the proliferation of racially restrictive covenants in the 1920s that would explicitly prohibit sales to African Americans.

Mason’s approach to real estate investment demonstrated sophisticated market analysis despite her illiteracy.

She held onto properties until they brought maximum returns, purchased strategically in areas poised for development, and diversified her holdings across multiple neighborhoods.

This investment strategy parallels that of other pioneering Black real estate entrepreneurs like Philadelphia’s Stephen Smith and San Francisco’s Mary Ellen Pleasant—who was arguably America’s first self-made Black millionaire, predating Madam C.J. Walker by decades.

Breaking Barriers Through Legal Precedent

The Mason v. Smith case of 1856 established crucial legal precedent in California and challenged the very foundations of slavery in free states.

Coming one year before Dred Scott v. Sandford—which ruled that Black Americans could never be U.S. citizens—Mason’s victory demonstrated that state courts could and would enforce constitutional prohibitions against slavery, even against the objections of slaveholders.

Judge Hayes’ decision to allow Mason to testify despite California’s law prohibiting Black testimony against whites was groundbreaking.

His ruling that enslaved people couldn’t give “free consent” to accompany their enslavers to slave states recognized the inherent coercion in the enslaver-enslaved relationship—a sophisticated legal reasoning that anticipated later civil rights jurisprudence.

The case freed 14 people and established that California courts would protect Black freedom even when it meant financial loss for white property owners.

This legal victory came amid California’s complicated relationship with slavery. Though admitted as a “free state” under the Compromise of 1850, California continued to tolerate illegal slaveholding, and many enslaved people remained in bondage until national abolition in 1865.

Mason’s willingness to challenge Smith in court—knowing she could lose everything and potentially be forcibly removed to Texas where she would be legally re-enslaved—required extraordinary courage.

Economic Foundation for Black Los Angeles

Mason’s wealth and philanthropy helped establish the institutional infrastructure of Los Angeles’ Black community at its inception.

In 1850, Los Angeles had only 12 Black residents; by 1860, that number had grown to 88; by 1880, 179; and by 1900, over 2,100. Mason arrived precisely when this community was taking shape, and her resources proved crucial to its development.

Her co-founding of FAME Church in 1872 provided Black Angelenos with their first house of worship and community center.

The church met in Mason’s home until she and Charles Owens purchased land on Azusa Street for a permanent building in 1888. FAME became the spiritual and organizational heart of Black Los Angeles, playing a pivotal role in the Great Migration that would bring thousands of Black Southerners to California in the early 20th century.

Today, FAME remains one of Los Angeles’ most influential institutions, with over 19,000 members and a history of producing civic leaders including Tom Bradley, Los Angeles’ first Black mayor.

Mason’s properties provided housing opportunities for newly arrived Black settlers. Unlike later periods when restrictive covenants confined Black Angelenos to specific neighborhoods, in Mason’s era Black residents could purchase property throughout the city—though concentrated in areas near Spring Street, San Pedro Street, and Central Avenue.

Mason and the Owens family strategically purchased land across Los Angeles, creating opportunities for Black wealth accumulation before such purchases became legally prohibited.

Her elementary school for Black children addressed the reality that California’s segregated school system often provided inferior education to Black students. Her traveler’s aid center supported the constant flow of Black migrants seeking better lives in California.

These institutions filled gaps in public services and created social capital that enabled community cohesion.

Key Contributions to Black Business in America

1. Demonstrating Midwifery as Pathway to Entrepreneurship

Mason’s medical skills provided the foundation for all her subsequent success. Midwifery was one of the few professions through which Black women could earn substantial income in the 19th century, combining traditional African and African American knowledge of herbal medicine with practical obstetric skills.

Mason learned these techniques from elder enslaved women, illustrating how enslaved communities preserved and transmitted specialized knowledge across generations.

Her fluency in Spanish—likely acquired during her years in California—expanded her client base to include Los Angeles’ large Spanish-speaking population, making her indispensable to Dr. Griffin.

Her reputation for delivering hundreds of babies safely earned her respect across racial and class lines. During the smallpox epidemic of the 1860s, Mason risked her own life to tend to the sick, further cementing her status as a community healer.

This model of leveraging medical expertise for economic independence was followed by other Black women entrepreneurs.

Clara Brown, who moved to Colorado during the 1859 Gold Rush, used her work as a nurse and laundress to accumulate over $10,000 by 1865, making her one of the wealthiest women in Colorado Territory.

Elizabeth Keckley, born enslaved in 1818 (the same year as Mason), learned dressmaking and used her skills to purchase her freedom for $1,200, eventually becoming dressmaker to First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln.

2. Strategic Real Estate Investment as Wealth-Building

Mason’s real estate empire demonstrated how property ownership could generate intergenerational wealth for Black families.

Her insistence that “the first homestead must never be sold” reflected a deep understanding that land ownership provided security, dignity, and assets that could appreciate over time.

This philosophy guided her entire investment strategy: acquire property in growth areas, hold for maximum appreciation, and pass wealth to descendants.

Her success came during a brief historical window when Black women could acquire property relatively freely.

By the 1920s, racially restrictive covenants became widespread in Los Angeles, explicitly prohibiting property sales to “persons of African, Chinese, or Japanese descent.” These covenants, combined with redlining and discriminatory lending, systematically prevented Black wealth accumulation through real estate for generations.

Mason’s portfolio eventually passed to her grandson Robert Curry Owens, who used this inherited wealth to become Los Angeles County’s wealthiest Black man.

The family held onto the Spring Street homestead until the Great Depression—nearly seven decades of continuous Black ownership in downtown Los Angeles, an achievement that became nearly impossible for subsequent generations.

3. Philanthropic Model of Community Reinvestment

Mason pioneered a model of wealth deployment that prioritized community welfare alongside family security. Her philosophy—”If you hold your hand closed, nothing good can come in. The open hand is blessed, for it gives in abundance, even as it receives”—guided her giving throughout her life.

Her philanthropy was intentionally multiracial, supporting churches attended by both Black and white congregants, feeding hungry people regardless of race, and providing medical care to anyone who appeared at her gate. This inclusive approach built social capital and goodwill that protected her business interests in a racist society.

Mason’s support for prisoners reflected a sophisticated understanding of systemic injustice.

At a time when Black people faced disproportionate incarceration and harsh treatment in California’s criminal justice system, Mason visited prisons regularly with gifts and aid, treating incarcerated people with dignity.

Her founding of the elementary school for Black children addressed educational inequality directly. Despite being illiterate herself, Mason recognized education as crucial for Black advancement—evidenced by her sending her grandsons (and possibly a daughter) to the Sanderson school for Black children in the Bay Area.

This commitment to education despite her own lack of formal schooling demonstrates remarkable insight into structural barriers facing Black communities.

4. Institution-Building for Long-Term Community Development

Mason’s co-founding of FAME Church represents her most enduring institutional contribution.

Churches served as the cornerstone of Black community life in the 19th century, providing not just spiritual sustenance but also social services, meeting spaces for political organizing, mutual aid networks, and cultural preservation.

FAME became the organizing center for Black Los Angeles’ civic life. During the Great Migration (1910s-1970s), FAME provided refuge from Southern racial violence and welcomed Black migrants seeking economic opportunity.

The church produced political leaders including Tom Bradley, who served as Los Angeles mayor from 1973-1993. FAME’s community activism during the 1960s Civil Rights Movement and after the 1965 Watts Riots demonstrated the enduring power of institutions Mason helped establish.

The church’s growth from Mason’s front parlor to a megachurch with over 19,000 members and its current magnificent building designed by renowned Black architect Paul R. Williams illustrates how one person’s initial investment can compound across generations.

FAME remains Los Angeles’ oldest Black-founded institution still operating today—a 153-year continuous legacy.

Legacy and What Readers Should Remember

Key Takeaways:

Courage to Challenge Injustice: Mason’s decision to sue for freedom required extraordinary bravery. She risked losing everything—possibly even being forcibly transported to Texas and re-enslaved—by challenging Smith in court.

Her willingness to fight, and Judge Hayes’ willingness to rule in her favor, demonstrated that even in deeply racist societies, legal systems could sometimes be leveraged for justice.

The Mason v. Smith precedent helped other enslaved people in California gain freedom.

Skills as Social Capital: Mason’s midwifery and nursing skills provided entry into California’s economy despite facing racism and sexism.

Her medical knowledge, learned from enslaved elders, proves how African American communities preserved valuable expertise across generations even under slavery’s brutality. Her Spanish fluency expanded her economic opportunities.

This combination of technical skill, cultural competence, and reputation for excellence created economic independence.

Financial Literacy Without Formal Education: Mason never learned to read or write, yet she performed sophisticated real estate market analysis, identified growth areas before they boomed, negotiated complex property transactions, and built a portfolio worth hundreds of millions in today’s dollars.

Her success challenges assumptions about the necessity of formal education for business acumen, while simultaneously highlighting how educational exclusion limited countless other talented Black people.

Intergenerational Wealth Creation: Mason’s insistence that “the first homestead must never be sold” reflected her commitment to building family wealth across generations.

Her grandson Robert inherited and expanded her real estate empire, becoming Los Angeles County’s wealthiest Black man.

This demonstrates how first-generation entrepreneurs create platforms for second and third generations to achieve even greater success—when legal systems permit wealth transfer.

Brief Window of Opportunity: Mason’s success occurred during a specific historical moment (1856-1920s) when Black people in California could own property relatively freely.

Beginning in the 1920s, racially restrictive covenants explicitly prohibited property sales to Black people, systematically preventing Black wealth accumulation through real estate.

Understanding this timeline illustrates how structural racism creates and closes economic opportunities.

Community Wealth vs. Individual Wealth: Mason didn’t just accumulate wealth for herself—she reinvested in institutions (FAME Church), infrastructure (schools, traveler’s aid centers), and individual people (feeding the hungry, supporting prisoners, housing the homeless).

This model of community-oriented wealth deployment created social capital that benefited thousands.

Gender Intersections: As a Black woman, Mason faced compounded discrimination.

Coverture laws prevented married women from owning property; racial laws prevented Black people from testifying in court; social conventions limited women’s economic roles.

Mason navigated all these barriers while illiterate, formerly enslaved, and raising three daughters alone. Her success required not just business skill but strategic maneuvering through multiple oppressive systems.

Modern Relevance: The Biddy Mason Charitable Foundation, established in 2013, continues her legacy by serving Los Angeles County’s 30,000 foster youth—populations disproportionately Black and Latino.

The Foundation provides scholarships (nearly $300,000 awarded since 2018), mentoring, and housing support, recognizing that enslaved people like Mason were effectively orphans, making foster care a natural extension of her humanitarian work.

Erasure and Recovery: Mason was buried in an unmarked grave for 97 years, and family disputes over her estate complicated her legacy.

Even today, many Angelenos don’t know who she was despite her foundational role in building their city.

This erasure reflects broader patterns of excluding Black women’s economic contributions from mainstream historical narratives. Recovery efforts—the 1988 tombstone, 1989 memorial park, 2013 charitable foundation—demonstrate ongoing work to restore her rightful place in history.

Comparative Context: While Mason is often called “the first Black real estate mogul,” Mary Ellen Pleasant in San Francisco may have preceded her, accumulating wealth as a “capitalist by profession” and using her riches to fund John Brown’s raid and support the Underground Railroad.

Both women operated in California during the same era, suggesting a network of Black female entrepreneurs leveraging Western opportunities.

Recognizing multiple pioneers prevents single-narrative histories.

Bridget “Biddy” Mason’s remarkable journey from enslaved midwife to California’s first Black female real estate magnate demonstrates the extraordinary business acumen, courage, and humanitarian vision that Black women have brought to American economic life since the nation’s founding.

Her legacy—embodied in FAME Church, the Biddy Mason Charitable Foundation, and the billions of dollars in downtown Los Angeles real estate she helped develop—reminds us that Black women’s economic contributions have been foundational to American prosperity, even when historical narratives have buried their stories in unmarked graves.

Mason’s life challenges us to recognize that barriers to Black entrepreneurship are not natural or inevitable, but rather the result of deliberate legal and social structures that, when partially lifted, reveal the extraordinary potential that exists within communities too long denied opportunity.

Resources for Further Study

Museums and Memorial Sites:

Biddy Mason Memorial Park

333 South Spring Street, Los Angeles, CA

80-foot concrete timeline wall by artist Sheila Levrant de Bretteville

https://www.laconservancy.org/learn/historic-places/biddy-mason-memorial-park/First African Methodist Episcopal Church (FAME)

2270 South Harvard Boulevard, Los Angeles, CA

https://www.famechurchla.org/ministries/about-fame-church/California African American Museum

Exhibits on Biddy Mason and Black California history

https://caamuseum.org/

Charitable Organizations:

Biddy Mason Charitable Foundation

Serving current and former foster youth in Los Angeles County https://biddymason.comhttps://www.facebook.com/TheBiddyMason/

Instagram: @biddy_masonBiddy Mason Foundation (Family Foundation)

https://biddymason.info/foundation

Primary Historical Sources:

Mason v. Smith (1856) Case Documents

https://blackpast.org/african-american-history/mason-v-smith-bridget-biddy-mason-case-1856/

https://blackartstory.org/2023/08/10/the-bridget-biddy-mason-case-1856/California Department of Justice - Reparations Report, Chapter 2: Enslavement (PDF)

https://oag.ca.gov/system/files/media/ch2-ca-reparations.pdf

Biographical Resources:

National Park Service - Bridget “Biddy” Mason

https://www.nps.gov/people/bridget-biddy-mason.htm

https://www.nps.gov/people/biddymason.htmNational Underground Railroad Freedom Center

https://freedomcenter.org/heroes/bridget-biddy-mason/Who is Biddy Mason? (Comprehensive Biography)

https://biddymason.com/who-is-biddy-mason/Wikipedia - Biddy Mason

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biddy_Mason

News Articles and Features:

Capital B News - “Biddy Mason Helped Build Downtown Los Angeles. Her Descendants Want Her Legacy Recognized”

https://capitalbnews.org/biddy-mason-history/Curbed LA - “Biddy Mason, one of LA’s first black real estate moguls”

https://la.curbed.com/2017/3/1/14756308/biddy-mason-california-black-historyMississippi Today - “1856: Biddy Mason secured freedom from slavery”

https://mississippitoday.org/2024/01/19/on-this-day-in-1856-bridgetmason-secured-her-and-her-family-freedom-from-slavery/Smithsonian Magazine - “The Trailblazing Black Entrepreneurs Who Shaped a 19th-Century California Boomtown”

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-trailblazing-black-entrepreneurs-who-shaped-a-19th-century-california-boomtown-180979635/

Academic and Research Articles:

Loyola Marymount University - “African American Women, Wealth Accumulation, and Social Welfare” (PDF)

https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=afam_facNorthwestern University Law Review - “In Search of the Common Law Inside the Black Female Body” (PDF)

https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1281&context=nulr_onlineAAIHS - “Slavery, Land Ownership, and Black Women’s Community Networks”

https://www.aaihs.org/slavery-land-ownership-and-black-womens-community-networks/

Medical and Midwifery History:

Midwifery Today - “Bridget ‘Biddy’ Mason: A Black Pioneer Midwife of Nineteenth Century Los Angeles”

https://www.midwiferytoday.com/mt-articles/bridget-biddy-mason-a-black-pioneer-midwife-of-nineteenth-century-los-angeles/UCSF Preterm Birth Initiative - “Biddy Mason, Trailblazer in Medical and Black History”

https://pretermbirthca.ucsf.edu/news/biddy-mason-trailblazer-medical-and-black-historyNatural History Museum - “Biddy Mason: Her Stand for Freedom”

https://nhm.org/stories/biddy-mason-her-stand-freedom

Black Los Angeles History:

Homestead Museum Blog - “The Black Pioneers of Los Angeles County, 1850-1900”

https://homesteadmuseum.blog/2023/06/16/the-black-pioneers-of-los-angeles-county-1850-1900-presentation-preview/Eric Brightwell - “No Enclave — An Overview of Black Los Angeles”

https://ericbrightwell.com/2012/01/30/no-enclave-an-overview-of-black-los-angeles/Wikipedia - History of African Americans in Los Angeles

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_African_Americans_in_Los_Angeles

First AME Church History:

Wikipedia - First African Methodist Episcopal Church of Los Angeles

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_African_Methodist_Episcopal_Church_of_Los_AngelesLA Sentinel - “FAME Church Celebrates 150 Years of Serving the L.A. Community”

https://lasentinel.net/fame-church-celebrates-150-years-of-serving-the-l-a-community.htmlSearchable Museum - “First African Methodist Episcopal Church of Los Angeles”

https://www.searchablemuseum.com/first-african-methodist-episcopal-church-of-los-angeles/ArcGIS StoryMaps - “First African Methodist Episcopal Church Los Angeles”

https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/9fc62ace418c4fd281089db90a3c5fc4

California Slavery and Freedom:

ACLU of Northern California - “California, a ‘Free State’ Sanctioned Slavery”

https://www.aclunc.org/blog/california-free-state-sanctioned-slaveryNational Archives - “Compromise of 1850”

https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/compromise-of-1850Wikipedia - Compromise of 1850

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Compromise_of_1850

Black Women in Business:

Amazing Women in History - “5 Successful Black Businesswomen In History”

https://amazingwomeninhistory.com/successful-black-businesswomen-in-history/Common Good Magazine - “Two Stories of 19th-Century Black Entrepreneurship”

https://commongoodmag.com/two-stories-of-19th-century-black-entrepreneurship/Urban Land Institute Los Angeles - “Biddy Mason, From Enslaved to Real Estate Mogul”

https://la.uli.org/womens-history-month-spotlight-biddy-mason-from-enslaved-to-real-estate-mogul/At & A Advisors - “5 Legendary Black Entrepreneurs: Stories of Success and Impact”

https://ataandeadvisors.com/5-legendary-black-entrepreneurs-stories-of-success-and-impact/

Video and Multimedia:

PBS - “Biddy Mason” (Boss: The Black Experience in Business)

https://www.pbs.org/wnet/boss/video/biddy-mason/YouTube - “Biddy Mason and the Making of Black Los Angeles” (UCLA Panel Discussion)

Contemporary Black Women Entrepreneurs:

WomenVenture - “Honoring Black Women Entrepreneurs: Stories of Leadership, Legacy, and Impact”

https://www.womenventure.org/news/honoring-black-women-entrepreneurs-stories-of-leadership-legacy-and-impact/J.P. Morgan - “Black Women Entrepreneurs: Growth and Headwinds”

https://www.jpmorgan.com/insights/business-planning/black-women-are-the-fastest-growing-group-of-entrepreneurs-but-the-job-isnt-easyGreenville Business Magazine - “Building a Legacy for the Next Generation of Black Women Entrepreneurs”

https://www.greenvillebusinessmag.com/2024/03/01/482986/building-a-legacy-for-the-next-generation-of-black-women-entrepreneurs

Additional Historical Context:

Wikipedia - Black-owned business

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black-owned_businessWikipedia - Mary Ellen Pleasant

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Ellen_PleasantLibrary of Congress - “Entrepreneur, Pioneer, and Philanthropist Clara Brown”

https://blogs.loc.gov/inside_adams/2022/10/clara-brown/